Central bankers have become laser-focused on crushing inflation. What could that mean for the economy and investors?

Overview

Investors found few places to hide from losses during the third quarter. Despite a brief summer rally, factors such as persistently high inflation and continued anemic economic growth weighed heavily on virtually all asset classes and market sectors. In addition, the war between Russia and Ukraine along with China’s continued Covid-19 lockdowns fueled fears about the global economy’s health.

Consider the performance of key areas of the financial markets during the quarter:

- The S&P 500 (down 4.9% during the quarter) posted its third consecutive quarterly loss—the index’s longest such losing streak since 2009.

- The MSCI ACWI index of global equity markets fared even worse, down 6.8%—with the non-U.S. component of the index down 9.9%.

- The yield on the 10-year Treasury note rose 82 basis points, contributing to the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond index’s 4.8% quarterly loss (as bond prices fall when bond yield rise).

Those quarterly losses were a continuation of what’s become a disappointing year for major asset classes: Year-to-date returns for the S&P 500 (-23.9%), the MSCI ACWI index (-25.6%), and the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond index (-14.6%) are all in the red.

That said, the U.S. labor market remained robust, with the latest unemployment rate (for September) hovering at its pre-pandemic low of just 3.5%. Falling oil prices during the quarter (down 23%) also helped ease gas prices for consumers.

A Single-Mandate, Single-Minded FED

Investors in the third quarter were confronted with the clearest evidence yet that when it comes to tamping down stubbornly high prices for goods and services, the Federal Reserve Board finally means business.

Indeed, it’s become obvious to us that the Fed is currently acting as a single-mandate central bank focused entirely on inflation. Officially, the Fed has two mandates or missions: to maintain both stable prices and maximum employment. Central bankers implement a monetary policy designed to keep inflation low and predictable while simultaneously promoting strong labor markets and economic growth.

Unofficially, however, the Fed has taken that labor market mandate off its agenda for the time being. As high prices have remained elevated and rising due to factors such as supply-chain problems and the Russia-Ukraine war, the Fed has pivoted to become fully focused on reducing inflation—significantly and aggressively, if necessary.

Some key examples of this single-minded focus on fighting inflation at all costs from the third quarter include the following:

- The Fed raised the federal funds rate, its key short-term interest rate, by 75 basis points in both July and September—an amount that Fed Chairman Jerome Powell himself characterized as “unusually large”—to a range of 3% – 3.25%.

- The Fed’s median projections show that it anticipates the target rate to be 4.4% by the end of 2022.

- In late August, Chairman Powell stated that “Without price stability, the economy does not work for anyone”—then noted that the Fed was prepared to impose economic pain to get inflation back to target. “We want to act aggressively now, and get this job done, and keep at it until it’s done,” said the chairman (echoing, perhaps inadvertently, former Fed Chair Paul Volcker—who also faced high inflation and whose autobiography is titled Keeping At It).

- In September, Powell said that the housing market is probably going to have to go through a “correction” to get supply and demand better aligned.

- Regarding the labor market, Powell noted “There is a very high likelihood that we will have a period of” what is “much lower growth…That is something that we think we need to have, and we think we need to have softer labor market conditions, as well. We have got to get inflation behind us. I wish there were a painless way to do that—there isn’t.”

- The Fed expects a 0.6 percentage point rise in the unemployment rate next year—a development that typically would prompt a rate cut to support the labor market—rather than the expected rate hikes the Fed is anticipating making in 2023.

NAVIGATING UNFAMILIAR TERRAIN

If it’s clear that the Fed is in full-on inflation-fighting mode, it’s equally clear that markets have not always been quick to believe and act with that fact in mind.

During the third quarter, for instance, the S&P 500 Index rallied roughly 13% from mid-July through mid-August partly because of some investors’ expectations that inflation may have peaked and that the Fed would be in a position to start cutting interest rates in 2023. However, it soon became clear to investors that inflation was still far too high—the Consumer Price Index rose 8.3% in August (year-over-year), down marginally from 8.5% in July—and that the Fed was not entertaining the idea of rate cuts anytime soon.

The S&P 500 responded by plummeting nearly 17% from mid-August through September.

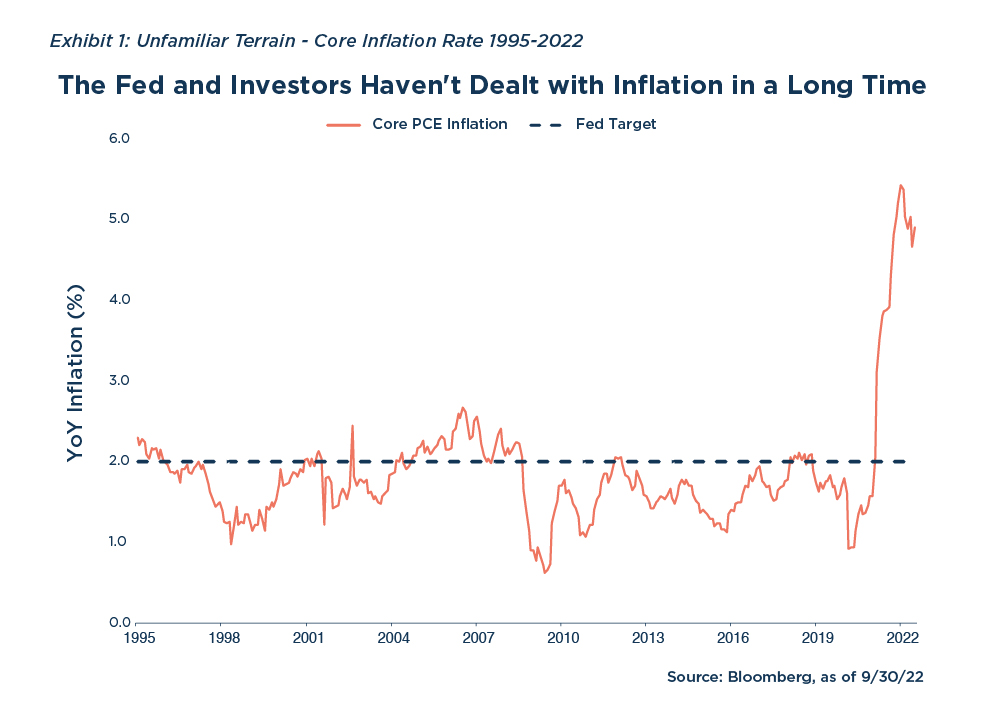

It’s not difficult to understand why the market and the Fed weren’t always on the same page. The current high inflation and rising interest rate environment is strange and unfamiliar to both investors and policymakers. As seen in Exhibit 1, inflation as measured by the Fed’s preferred gauge, Core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) has been benign for nearly the past 25 years—averaging just 1.7% annually from 1995 through 2019 and rising above 2% just about one-quarter of the time during that period. Many investors have never experienced a spike such as the one we’re currently seeing.

For much of this time, the Fed could effectively ignore inflation safely and instead focus on supporting the labor market and overall growth. That’s exactly what it did when it cut interest rates following the 2008 global financial crisis, and later left rates at historically low levels (2016) or cut them further to help shore up growth (2019). As Chairman Powell stated back in 2020: “A robust job market can be sustained without causing an unwelcome increase in inflation”—a very different point of view than his latest comments convey.

The upshot: Until very recently, the Fed had been operating under a decision-making framework in which rates could easily be cut to spur additional growth because inflation was essentially a non-issue. Over those many years, investors became used to buying risk assets (knowing that Fed policy was likely to stay accommodative) and leaping into the market whenever there was a downturn. Indeed, “buy the dip” became something of a mantra to many investors—an action often taken without question because it usually worked. Likewise, the market often reacted positively to bad economic news because it likely meant more accommodative monetary policy from the Fed.

Today, of course, that framework is fundamentally different—and some old models of investment decision-making are no longer as effective as they once were. Buying the dip now is likely to mean there will be another dip to buy tomorrow and another the day after that. Assets and market sectors that benefit from a low-rate environment are now facing the headwinds of higher borrowing costs, wage pressures due to a tight labor market, and demand uncertainty due to higher prices being shouldered by consumers. In addition, bad economic news is viewed as bad news that will drive the Fed to tighten its policy rather than loosen it.

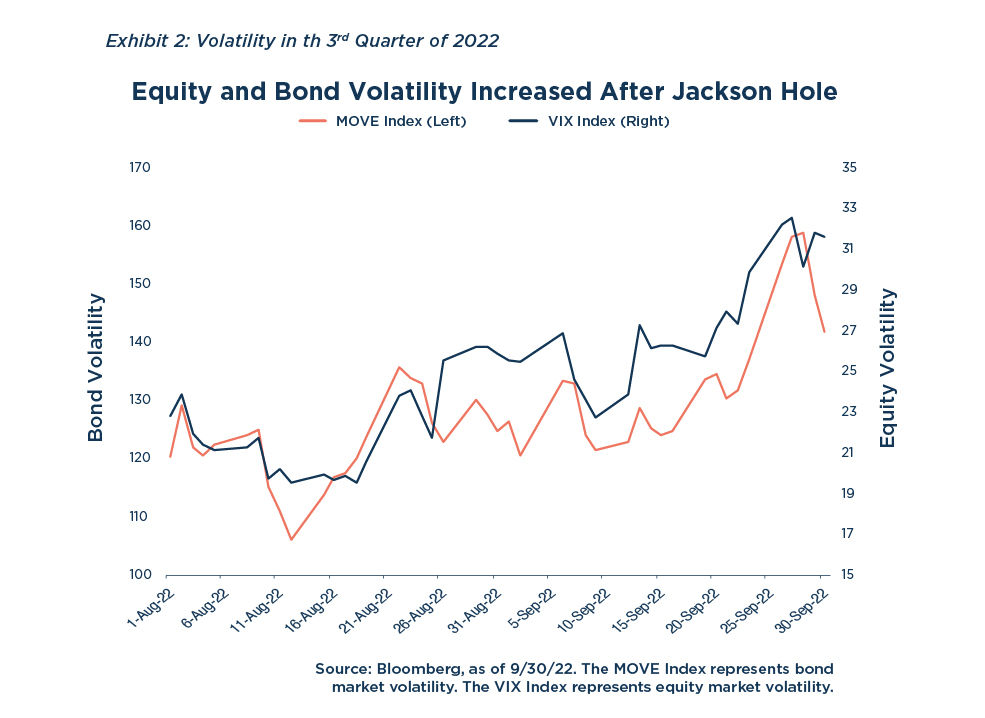

Ultimately, the situation has flipped upside down—and done so in short order. That’s forcing market participants across the board to retrench and shift their thinking on the fly. One result: Implied volatility of U.S. Treasuries and equities have spiked in recent weeks, as seen in Exhibit 2.

It’s also worth noting that this is many people’s first experience managing their money in a world of stubbornly high prices and a Fed that’s aggressively raising interest rates to combat them. Pivoting to a mindset that can chart a course through this particular fog can be challenging if you haven’t done it before.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE "FED FLIP"

The inflation-obsessed Fed and its monetary policy moves have significant and important implications for markets in the coming months. Chief among them:

- Expect “higher for longer.” Even as some aspects of inflation (such as oil prices) have been easing, other key components of inflation—such as housing, food, and wages—are proving to be “sticky,” causing the overall inflation to remain uncomfortably high. As long as inflation appears to be well-entrenched in the economy, look for the Fed to maintain relatively high interest rates and raise rates to above 4%. We view the probability of the hoped-for “pivot” back toward rate cuts and a focus on supporting growth to be low to virtually non-existent in the medium term.

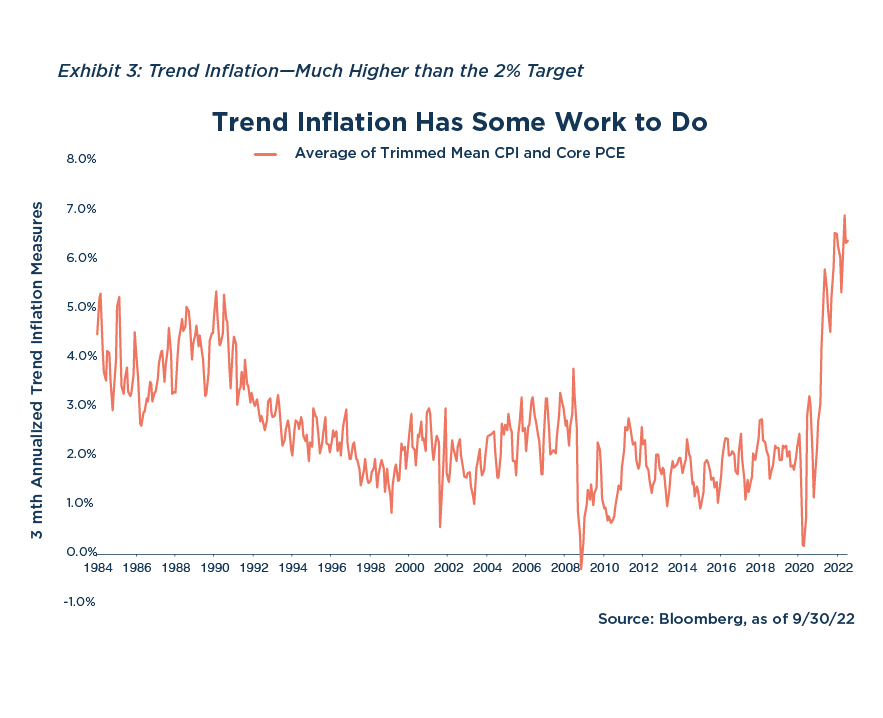

- A well-established trend is needed for things to change. What, exactly, would cause the Fed to conclude that its restrictive monetary policy is working as intended? One month of positive news on inflation will not be adequate. Instead, we believe the Fed will want to see at least three months in which the month-over-month inflation rate (adjusted on an annualized basis) comes in at around the Fed’s long-term target of 2%. Note that this is different from the headline year-over-year CPI data commonly reported in the media. Rather, this would be a consecutive three-month trend of 2% (or so) inflation on an annualized basis—or 0.2% (or less) on a month-by-month basis. One bad number at any point would essentially “restart the clock.”

A look at where we stand today suggests that this 2% trend could be a long time coming. Exhibit 3, which shows the average of two separate measures of inflation, shows a short-term trend of around 6%. Clearly, the Fed has more work to do.

- “Don’t Fight The Fed’—still true, but different. The old saying “don’t fight the Fed” admonishes investors to align their portfolios with current Fed monetary policies rather than against them. It’s one of those mantras noted above that investors became very comfortable with during the past decade.

The good news: Don’t fight the Fed can still be good advice. But aligning investments with today’s Fed seeking tighter financial conditions means something different than it used to. “Sell into rallies” may occur more frequently than “Buy the dip.” Also, emphasizing high-quality credits and being judicious with junk bond investments until inflation is contained currently aligns with Fed policy. We believe a cautious, flexible, and dynamic approach to portfolio allocation could be advantageous as the Fed digests new inflation and demand data each month.

- We don’t think it’s the 1970s all over again. The media is quick to note with each new inflation report that the last time prices were this high was during the 1970s—a period of stagflation, gas shortages, and deep economic pain for many. Fed policy during that time has often been characterized as “stop and go” because the Fed would hike rates to fight inflation, then cut rates only to hike them again down the road.

The current Fed members appear to have learned the lessons of that decade and are not engaging in short-term policy pivots. To the contrary, they are resolved to keep rates at levels that they think can quell inflation—even, as they have stated, if doing so will end up causing economic pain. On the final day of the third quarter, Fed Vice Chair Lael Brainard stated that “monetary policy will need to be restrictive for some time to have confidence that inflation is moving back to target” and that “we are committed to avoiding pulling back prematurely.”

WHAT ABOUT A RECESSION?

One big, recurring question on investors’ minds in the wake of the Fed’s battle with inflation is whether the economy is headed toward (or perhaps even already in) a recession.

Clearly, the Fed believes that inflation must be brought under control in the short term in order to stabilize the economy and promote growth in the medium term. While that could cause a recession, this is a trade-off the Fed is willing to make. Failure to moderate inflation would almost certainly cause much greater problems, akin to what we saw during the 1970s—rampant unemployment and a level of volatility that makes it essentially impossible for businesses, governments, and individuals to make financial decisions with any real clarity.

Another key fact that often gets overlooked is that recessions do not all “look and feel” the same—their size, depth, and impact can range from mild to strong. This is often forgotten by investors today, in part because the last major recession we experienced in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis was so extraordinarily severe by historical standards. What’s more, certain economic conditions—such as the inflation rate and GDP growth—preceding past recessions have often differed significantly (as we recently noted in our study “What Constitutes a Recession?”). Predicting recessions based on one or two indicators is therefore not a consistently reliable approach.

We certainly have cause for concern today given the Russia-Ukraine war, interest rate hikes, a yield curve inversion, and falling GDP growth. That said, according to Bloomberg, corporate earnings have been robust—one measure of US aggregate profit margins recently posted its best reading since 1950—and the labor market remains healthy. Both suggest a recession has not begun.

Additionally, the current strong labor market could help prevent soaring unemployment should a recession occur. Given a large number of job vacancies and continued tight labor conditions, businesses may be less inclined to lay off their workers if the economy slows further—and instead look to reduce costs in other ways.

Conclusion

In the coming months, Fed policy and statements will likely continue to have an oversized impact on investor sentiment and the performance of stocks, bonds, and other asset classes. That impact will feel particularly strong if investors’ predictions about the state of the economy and the direction of interest rates once again diverge from those of the Fed.

Given the continued uncertainty and volatility, we are maintaining a relatively defensive positioning for the time being, emphasizing areas of the market such as high-quality fixed-income securities, value stocks, high-dividend-paying equities, and generally lower volatility stocks that tend to hold up well during market sell-offs.

For additional insights on the quarter and the road ahead, watch our Q3 webcast here: https://www.horizoninvestments.com/2022-q3-focus-webcast/

Disclosure

The commentary in this report is not a complete analysis of every material fact with respect to any company, industry, or security. The opinions expressed here are not investment recommendations but rather opinions that reflect the judgment of Horizon as of the date of the report and are subject to change without notice. Opinions referenced are as of the date of publication and may not necessarily come to pass. Forward-looking statements cannot be guaranteed.

We do not intend and will not endeavor to provide notice if and when our opinions or actions change. Horizon Investments is not soliciting any action based on this document. This document does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security or product and may not be relied upon in connection with the purchase or sale of any security or device. The investments recommended by Horizon Investments are not guaranteed. There can be economic times when all investments are unfavorable and depreciate in value. Clients may lose money.

The S&P 500 or Standard & Poor’s 500 Index is a market-capitalization-weighted index of the 500 largest U.S. publicly traded companies. The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index is a broad-based benchmark that measures the investment grade, U.S. dollar-denominated, fixed-rate taxable bond market, including Treasuries, government-related and corporate securities, mortgage-backed securities, asset-backed securities, and collateralized mortgage-backed securities. The MSCI ACWI Index is designed to represent the performance of the full opportunity set of large- and mid- cap stocks across 23 developed and 24 emerging markets. References to indices, or other measures of relative market performance over a specified period of time are provided for informational purposes only. Reference to an index does not imply that the any account will achieve returns, volatility or other results similar to that index. The composition of an index may not reflect the manner in which a portfolio is constructed in relation to expected or achieved returns, portfolio guidelines, restrictions, sectors, correlations, concentrations, volatility or tracking error targets, all of which are subject to change.Individuals cannot invest directly in any index.

Information has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed.

Horizon Investments is an investment advisor registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. More information about Horizon’s investment advisory services can be found in our Form ADV Part 2, which is available upon request.

Horizon Investments and the Horizon H are registered trademarks of Horizon Investments.

© 2022 Horizon Investments, LLC.

HIM102022

NOT A DEPOSIT | NOT FDIC INSURED | MAY LOSE VALUE | NOT BANK GUARANTEED | NOT INSURED BY ANY FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AGENCY