The truth is, individual investors today don’t care as much about exposures as they do outcomes. They’re asking how to build portfolios that will help them achieve their financial goals.

“I Just Wanted Some Granola”

Have you ever stood in a grocery aisle trying to decide which brand of cereal to buy? Rich in fiber. Low in sugar. Organic. Non-GMO. Allergen-free. Shredded. Nutty clusters. Fruity flakes. You get the idea. Choosing from the sheer number of brands and types of cereal available today can make your head spin. Barry Schwartz’s book, The Paradox of Choice: Why More is Less, published in 2004, gave insight into this modern phenomenon.

Feeling overwhelmed by options in the grocery aisle is a near-universal experience, but this paradox of choice also applies to selecting investment products. The dramatic increase in available products, from fewer than 1,000 mutual funds in the mid-1980s when ETFs didn’t even exist to today’s 25,000-plus mutual funds and 2,500 Exchange Traded Funds, makes selecting the right investments a potentially confusing, and possibly paralyzing, endeavor. There’s even a term for it: “decision paralysis.”

Categorizing and ranking investment products

As investment products proliferated, consumers grew more overwhelmed. That’s when navigation of the investment universe became big business. Firms began creating ranking systems — shortcuts if you will — to help consumers better understand the investment products available to them. In doing so, these systems became akin to a “Consumer Reports” for the investment industry. The problem is, instead of creating a shortcut for financial advisors and individuals to choose the most appropriate investment, these services actually created a challenge: how to use a categorization system that’s tilted towards institutions to solve for the investment goals of individuals.

The truth is, individual investors today are no longer likely to ask which small-cap value fund or large-cap growth fund they should buy. They don’t care as much about exposures as they do outcomes. They’re asking how to build portfolios that will help them achieve their financial goals. And because their goals are time-constrained, they may not benefit from focusing on the statistical properties that drive the output of these categorization services.

Individuals differ from institutions

Is the same investment that is “right” for an institution “right” for an individual? The simple answer is: sometimes. Under the right circumstances. Depending on the individual’s situation. As in many things, the true answer is complex.

Individuals and institutions face many different questions, objectives and risks. Two of most notable differences are 1) their investment horizon (time) and 2) their objective (the success equation, i.e., return/risk). Advisors know this all-too-well. Successful financial planning requires a balance of making sure the right product is used at the right time for the right reason. But time horizon challenges can create statistical uncertainty for the individual investor that institutions may not be subject to traditionally.

In fact, an individual’s investment objective and personal timeline can cancel out the statistical “greatness” of one fund and give it to another one that’s “less great” in a categorization scoring system. For example, a highly ranked fund with the best traditional (i.e., institutional) return/volatility characteristics in a given category may severely underperform in a declining market environment. While the high rating may pay off in the long term as the fund outperforms in an up-market, the individual may not want (or be able to withstand) this specific market experience. The risk is that they’ll end up purchasing it anyway, based on a ranking that directs them into exactly what they’re trying to avoid.

The individual (through their financial advisor) is left with questions:

- When will using the shortcut of these ratings systems work?

- Where should caution exist when considering these ratings?

- Where should additional due diligence be done when the shortcut doesn’t provide an advantage?

Who are consumers of financial products?

Any conversation about consumer needs has to consider exactly who those consumers are. Typically, consumers of financial products today are categorized into three groups: institutions, professional investors (e.g., Financial Advisors), and individual investors.

Because Financial Advisors and individual investors are aligned in their goals, we think it’s easier to segment consumers into just two groups: institutions and individuals. To understand whether and when investment product categorization and rating services are helpful to these two groups, you have to first understand their needs and how they might differ.

Institutions — sovereign wealth funds, pension plans, university endowments, and large corporations — are some of the biggest investors in the world. These entities typically have extremely large investment accounts and essentially infinite investment horizons.

This infinite investment horizon is a crucial detail to understanding the optimal investment behavior for this group: diversification among different investment exposures is the key risk mitigation tool, because volatility can hamper both long-term investment performance and also produce more disparate investment paths for individuals who may be entering and exiting the plan at different times.

Individual investors — parents, grandparents, employees, small business owners, retirees — face a very different set of investment problems than institutions, which don’t have to worry about retiring or sending a kid to college. The investment problems individuals face are defined goals within finite time frames, like buying a house, funding college for their children or grandchildren, retirement.

This difference between individuals and institutions can be oversimplified to: “Institutions don’t really have a timeframe for their investments, but individuals do.” While different, both individuals and institutions need to navigate the myriad of investment options available to them to create the best solutions for their respective goals and time horizons.

However, there is no turn-key solution. Each has their unique needs, objectives and risks. It’s important for professionals serving either group to understand the key distinctions between them and be able to explain the strengths and weakness of the investment tools they may use.

Guidelines for effectively using these systems

Horizon believes there are underlying principles that must hold true for today’s categorization and rankings systems to be useful to individuals striving to choose among different investment options.

Guidelines for using categorization and rankings systems

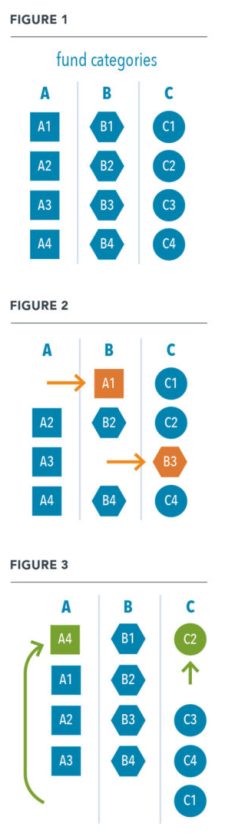

- Categories must be homogeneous (i.e., similar products are grouped in the same category). See Figure 1 that illustrates categories A, B, C are homogenous

- Categories must be stable (i.e., investments should not jump categories without a change in investment philosophy). See Figure 2 that illustrates funds moving between categories

Every fund in each category has an equal chance at success. See Figure 3 that illustrates equal success within each category

In practice, categorization and ranking services are just quantitative groupings of investment products — mathematical shortcuts for making sense of the myriad of available investment product. While these shortcuts are neither good nor bad, to use them effectively, investors should understand what underlies them. But precisely because these services use mathematical groupings, they’re subject to the normal issues inherent in statistical distributions.

Ideal conditions versus real life

We’ve described an ideal set of characteristics for a ranking methodology, but the ideal doesn’t exist in real life. Financial professionals, like advisors, are left to figure out where the application of the methodology makes sense, where it drifts from conventional understanding, or where it simply misses the mark.

Not only do we think it’s vital to understand the construction principles of these categorization and ranking services, we have to also be aware of their potential limitations. Armed with the knowledge that categories are merely a mathematical construct, it’s inevitable that a category may contain funds not fully represented by the math, i.e., “tails.” While most funds may be clustered around certain mathematical inputs/variables (e.g., this can explain index trackers), other funds simply “never belong” from a statistical viewpoint.

So while in the “ideal” state funds wouldn’t “move” between or away from categories, in the “real” world we all know that they do. But this only addresses inclusion criteria — or why certain investment products are included in certain categories. What about the use of the category itself? In order to use the category we will need to identify two additional issues: relevance and consistency.

Relevance

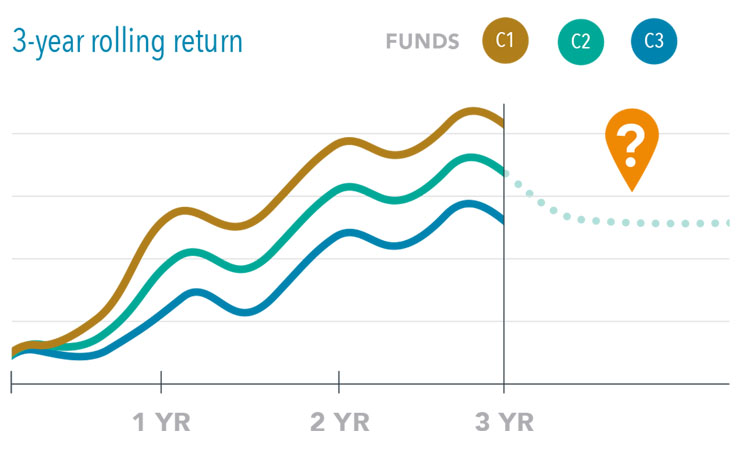

Is the specific time period used to judge the investment product in any category (e.g., the last 3 years) a reliable barometer to forecast the future of those same investment products?

Consistency

Are the category’s characteristics internally described across every fund in any type of market environment? Are funds in the same category exposed to similar risk factors?

The first issue of relevance has to do with the time segment used to define the category or ranking. The best example may be whether to include the market performance of 2008-2009. Whether or not that performance is included obviously generates different scenarios for potential return outcomes of the investment product being evaluated (and different conclusions as to the viability of that particular investment product).

For example, consider a product that is taking less risk than its peers in its category, but the time period being used to evaluate it is a strong, upward-trending market. This particular fund may appear to underperform its peers, but only for the time period represented. Further, while the mathematical shortcut describing this product’s historical state of underperformance is obviously correct, it doesn’t speak to a potential future state. You’ve heard many times before: “Past performance is no guarantee of future results.”

The second issue deals with how all investment products in a specific category can function in every given market environment, so as to provide a more accurate distribution of outcomes for the category. Do the risk factors present during a defined time period remain stable during different types of market environments? For example, consider a well-performing tactical income fund in a stable rate environment. Now consider that same fund having the ability to exhibit flexibility in how it might approach rising or falling rate environments. How well does its category, and category of peers, characterize this flexibility?

Useful shortcuts for some more than others

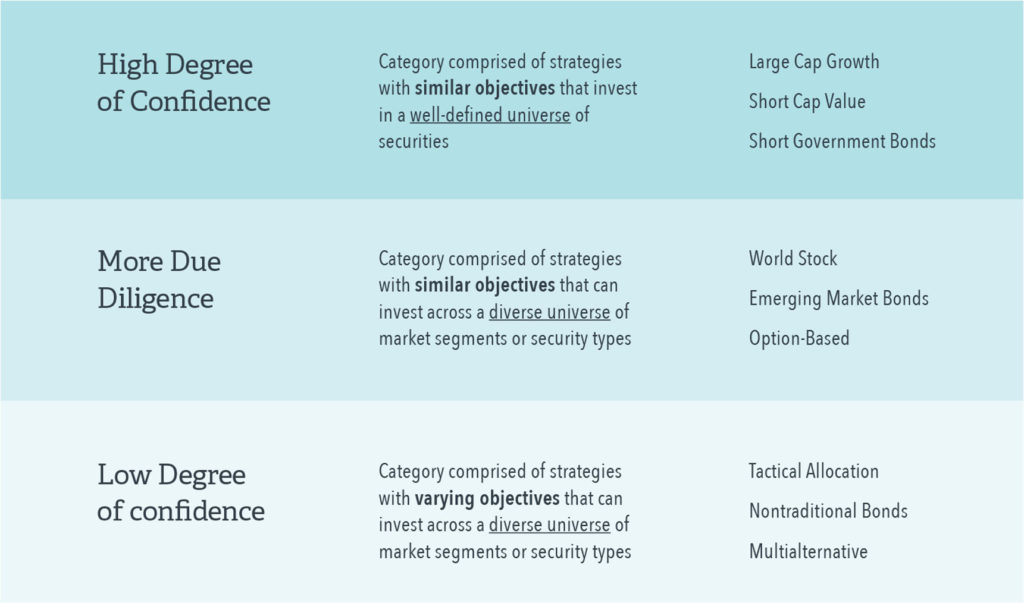

We’re not saying that rankings or categorizations aren’t useful; in fact, the opposite. These ranking and categorization shortcuts are helpful to guide advisors to where extra work may be needed. And we strongly believe these services are important to understanding how to construct diversified portfolios using funds from “stable categories,” like large growth.

While there are exceptions to every rule, rankings appear to be more useful for some categories than others. There are guidelines associated with investment categorizations, and funds inside these categories, that are cogent, while others are more problematic and could potentially lead to confusing results [Table 1].

The future: reimagine investment categorization

Wouldn’t it be better if categorization and scoring solutions were more aligned with the planning process of helping individuals realize their financial goals? While today’s services can help with portfolio construction, they simply weren’t built for goals-based planning.

The factors driving financial planning — time horizon, circumstances, goals, obligations — are fundamentally different from those used to first develop these services in the 1980s. Which is why it’s so critical for financial advisors and other fiduciaries to know when to use these ranking services and when to set them aside. Like any shortcut, there are pros and cons to filtering large data sets based on mathematical statistics. We encourage you to consider the guidelines we’ve provided and be judicious, even cautious, when using ranking services for planning purposes.

Table 1

This information is for educational use only and should not be considered financial advice. Forward looking statements cannot be guaranteed. The opinions expressed are those of Horizon Investments and are subject to change without notice. All investing involves risk, and no investment is guaranteed. Clients may lose money.

© 2020 Horizon Investments, LLC is an investment advisor registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. More information about Horizon’s investment advisory services can be found in its Form ADV Part 2, which is available upon request. HIM032020